The implications of war for the US stock market

Redacción Mapfre

By invading Ukraine, Russia has created a humanitarian crisis. At a time when heart-wrenching news footage reminds us daily that innocent people are losing their lives, discussing the market implications of such devastation can feel unseemly. But because we’re responsible for doing our best to preserve and grow capital for MAPFRE’s clients, now is exactly the time to talk about those implications.

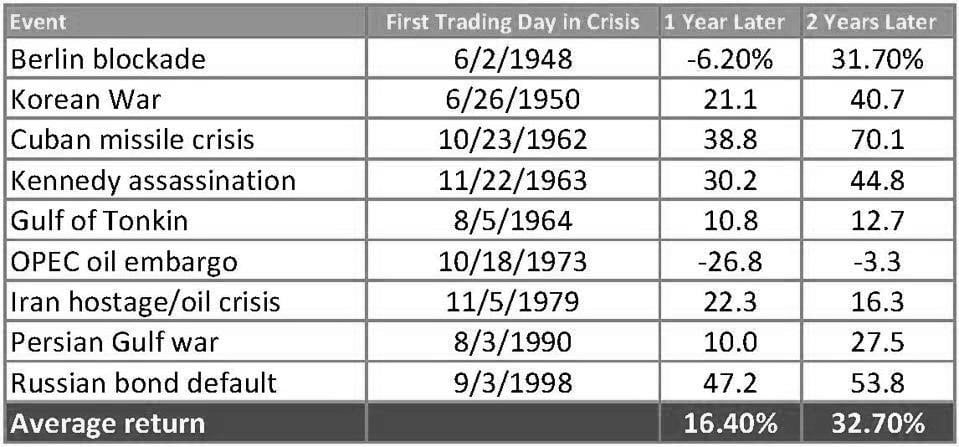

As we advised our clients in the aftermath of 9/11, during the 2008 financial crisis, and again in March 2020, when COVID was raging and the stock market was tanking, the most important thing investors can do during a crisis is to simply not panic. Stock market history supports this assertion. Dreman Value Management examined the major geopolitical events since World War II and found that on average the Dow Jones Industrial Average was 16.40% higher 1 year later and 32.7% higher 2 years later:

Markets Have Been Resilient in the Wake of Crises

Source: Dreman Value Management, L.L.C.

The equity market often rebounds well before a crisis ends. According to LPL, when COVID was raging, the S&P 500 fell 33.9% from its February 19, 2020, peak to its March 23, 2020, low—and then took only 5 months to recover its losses, finishing the year up 16.3% during the throes of the pandemic. We think Warren Buffett said it best in his famous New York Times op-ed published during the 2008 financial crisis:

Or think back to the early days of World War II when things were going badly for the United States in Europe and the Pacific. The market hit bottom in April 1942, well before Allied fortunes turned. Again, in the early 1980s, the time to buy stocks was when inflation raged, and the economy was in the tank. In short, bad news is an investor’s best friend. It lets you buy a slice of America’s future at a marked-down price.

Over the long term, the stock market news will be good. In the 20th century, the United States endured two world wars and other traumatic and expensive military conflicts; the Depression; a dozen or so recessions and financial panics; oil shocks; a flu epidemic; and the resignation of a disgraced president. Yet the Dow rose from 66 to 11,497.

You might think it would have been impossible for an investor to lose money during a century marked by such an extraordinary gain. But some investors did. The hapless ones bought stocks only when they felt comfort in doing so and then proceeded to sell when the headlines made them queasy.

Today people who hold cash equivalents feel comfortable. They shouldn’t. They have opted for a terrible long-term asset, one that pays virtually nothing and is certain to depreciate in value. Indeed, the policies that government will follow in its efforts to alleviate the current crisis will probably prove inflationary and therefore accelerate declines in the real value of cash accounts.

Reminisce of The Dotcom Bubble

As of March 1, the S&P 500 has lost over 9.5% YTD, but the performance of the “average” stock goes beyond that simple statistic, with many companies having declined 30% to well over 50% from their highs. Just last week the S&P 500 posted 64 new 52-week lows and the Nasdaq composite recorded 974 new 52-week lows.

In particular, some of the pandemic highflyers, which led the market for most of 2020-2021, have been decimated. Infatuated by their high growth rates and large total addressable markets, Wall Street accorded them absurdly high valuations despite their lack of profitability. Now Peloton has dropped from over $160 a share to just $27; Zoom, which once sold for more than $550 per share, trades at $122; and Robinhood, a brokerage firm providing free trades to largely millennial customers, is selling for $11.77 per share, down from $85.

The ARK Invest Innovation ETF (managed by Cathie Wood) is the poster child for the pain felt in the market’s most speculative areas. ARK fund shares gained almost 200% during the past 5 years, but most of those gains came in 2020, and the fund is now down more than 54% from its all-time highs in February 2021 (and, as of March 1, down ~27% in 2022 alone)—performance that Edward Harrison of Bloomberg calls “eerily similar” to the dotcom bubble and bust. Despite ARK’s recent poor showing, Ms. Wood’s long-term record is quite strong, but unfortunately most of her investors haven’t done so well: according to Bespoke Investment Group, the average investor in five of ARK’s ETFs is nursing a ~27% loss.

Some might start seeing bargains with so many former market leaders down so dramatically, but we, too, find the current climate “eerily similar” to the dotcom crash, when former market darlings plunged by 50%-75%, with most never returning to anywhere near their former highs. We also note that amid the carnage of the crash, we produced some of the best absolute and relative returns in our history. Past performance is never a guarantee of future results, but we agree with Mark Twain’s observation that “history never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme.”

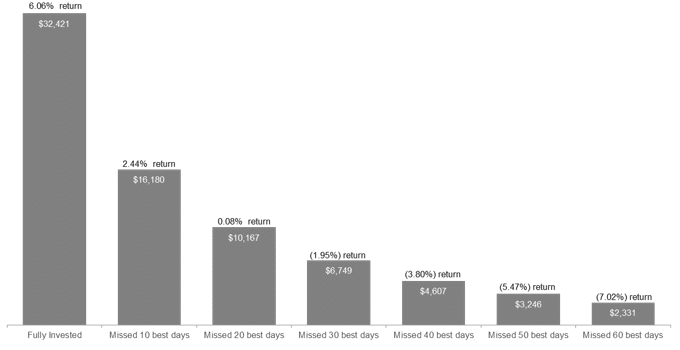

In addition, stocks have shown staggering volatility since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. These difficult conditions could last for some time, but that’s no reason to flee the market. History teaches us that markets tend to be resilient, often sharply advancing in the wake of a crisis. What’s more, because the penalty for missing the market’s best days can be steep, trying to time the market (or a crisis) is likely to be a very costly mistake. As the following chart shows, over the long term, missing just the 10 best days of the market can cut investors’ returns by more than half of what they would have gained by remaining fully invested.

Impact of Being out of the Market

Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management analysis using data from Bloomberg.

No one can be completely insulated from a crisis, but the names owned within The MAPFRE Forgotten Value Fund should be insulated to a large degree from the war in Eastern Europe. Investors might even see opportunity in the uncertainty that is pressuring these companies’ share prices. Horrifying as the current headlines are, their long-term effect on the outlook for our Forgotten Value stocks (many of which do little to no business in Eastern Europe) will likely be negligible.

Jonathan Boyar, CEO at Boyar Value Group