Sustainable values: the opportunity presented by new regulation

Redacción Mapfre

It is a common practice in the world of asset management to lump together all types of sustainability analysis under the ESG prism, but this is not entirely correct. Sustainable does not always have a good ESG rating, and companies with better ESG ratings may not always qualify as sustainable. Similarly, there is a tendency to trivialize and simplify ESG analysis itself. If we go a bit deeper, we see that there is a wide range of possibilities depending on the scope of our analysis and the objective we set ourselves. For example, the analysis carried out by a risk department to calculate risks should not be the same as that carried out in asset management with the intention of integrating it into an investment process aimed at optimizing returns. Or that carried out by corporations for the publication of non-financial information. Obviously there are similarities and shared content, but it is important to highlight the difference.

This lumping it all together in recent years as this topic come to the forefront has led to the adoption of regulatory measures to avoid “greenwashing” and to the creation of a sustainable reporting framework for the different areas of application. If we focus on the field of asset management, it is true that those of us traditional managers who remain within the bounds of Article 6, without a specific ESG/Sustainable mandate, are to some extent exempt from obligations arising in this flood of regulation. However, we will be exposed to these changes in an indirect way. Regulations are coming on strong. The changes being made in Europe go far beyond mere contractual and reporting obligations, and far-reaching changes are being considered in the field of capital markets. Therefore, our obligation is to stay as informed and aware as possible in the midst of what some analysts consider to be one of the most disruptive regulations in the history of finance. And as the Spanish proverb goes, “A rio revuelto, ganancia de pescadores” (it's good fishing in troubled waters).

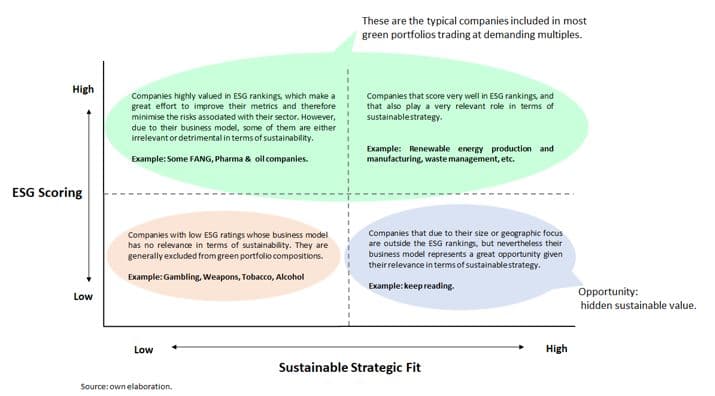

To envision all these changes in context, it is important to highlight one of the most widespread criticisms of the liberal use of the term "sustainable." The lack of regulation in this regard has meant that for several years ESG ratings have been used indiscriminately for managing almost all sustainability-related issues. It is very common to see companies with high ESG ratings but belonging to sectors with little or no weight in the field of sustainability.

So much so that an examination of the most frequently named companies in portfolios related to sustainable issues at a global level, we find in the top ten names such as Roche, Novo Nordisk, Google or Visa, all of them with excellent scores in the most popular ESG rankings. When this same filter is applied to Europe, we find in sustainability rankings names as questionable as Loreal, Astrazeneca or Adidas. And not only that; if we look only at exclusion criteria, we are likely to see "sustainable" liability management portfolios with oil companies among their components. In all cases with excellent ESG scores.

Is this wrong? Far from it. An oil company (and any other company) can have excellent management of environmental, social and corporate governance aspects. Therefore, it deserves the score, but given its business model, it is far from being considered sustainable.

It is this incongruence, which is much more common than one might expect, that we are going to address. As we mentioned in the previous point, the concept of sustainability is something much broader than sheer ESG analysis. The lack of regulation in this regard has encouraged arbitrariness with regard to an already ambiguous concept such as sustainability. This subjectivity in the definition of what is and what is not sustainable has allowed everything with a good ESG rating to become part of sustainable portfolios. This is where the European taxonomy comes into play.

If you want to be green, forget ESG ratings: you have to be taxonomic. This regulation defines the list of economic activities that, based on a series of technical, social and compatibility criteria, can be considered to be environmentally sustainable. Therefore, it eliminates arbitrariness in the concept of sustainability at a stroke of a pen, and clearly defines what is and what is not officially sustainable.

The taxonomy is not free of controversy, as it is an instrument developed with the sole objective of defining a sustainable future. It is a tool with a “single mandate” to conform to a decarbonization target, so it does not measure the economic and social costs of this path to a sustainable future. However, it is not the purpose of this article to debate whether this regulatory pressure towards an accelerated and forced ecological transition is the best tactic, or not, in economic, strategic terms, and so on. That is another (very interesting) debate that would take us a long time to address. The only thing that is clear is that it is the central task of the European regulator to incentivize “capital allocation” towards the main objective of decarbonization of society, regardless of the cost or consequences. The objective is so ambitious that, to paraphrase one of its promoters, it “aims to lay the foundations for defining the economy of the future.”

In short, it is a very disruptive regulation, which to some extent will change the rules of the game in many areas, (of course also in the context of asset management). Hence, in my humble opinion, even if one does not have a specific sustainability mandate, it is better to respect and understand it than to ignore and underestimate it.

Therefore, to the already well-known ESG analysis, we are adding the taxonomy component, which we have christened with the name “sustainable strategic fit.” It should be recalled that the taxonomy is not based on ESG rankings, but on purely technical criteria for activities considered necessary to achieve environmental objectives. Therefore, incorporating this variable to the already commonly used ESG notes, three major groups are defined in the field of sustainable investment:

It’s good fishing in troubled waters. In this new regulatory environment a group of companies is emerging that have the potential to be officially considered sustainable. But are not under the radar of large thematic funds, sustainable managers or ESG analysts and therefore do not enjoy the premium associated with that feature. The interesting thing about the taxonomy is that it includes a series of economic activities that do not enjoy traditional green labeling, but which the regulations deem critical (at least for a time and provided they meet certain requirements) for achieving environmental objectives. Activities such as cement, steel and aluminum production, building construction and renovation, water and waste management, construction of low-emission transportation infrastructure, data processing and storage and many others, are "eligible" activities. That is, they can be officially considered environmentally sustainable regardless of the ESG ratings they receive. And the list continues to grow, as it is in full swing, with more environmental targets being set.

Therefore, a very interesting opportunity is arising to seek out investment ideas, since the Taxonomy is not just a classification. As we have explained above, it is the regulatory lever to incentivize the flow of capital to the chosen activities. Therefore, a series of advantages are to be granted to these activities, such as advantageous financing, access to European funds and all kinds of governmental support. In addition, from a commercial point of view for asset management, it will be the key to obtaining the green labels that will mean being able to prioritize these investment products in customer suitability tests.

And yes, we all know (or almost all of us know) how capital cycles work. Directing the flow of capital to specific activities can be a double-edged sword. This incentive can lead to an oversupply in some sectors due to their “sustainability advantages” and it may become more difficult to find companies capable of maintaining their profitability in a competitive environment. But this is where analysis and methodology come into play: Porter's 5 forces, and the competitive advantages of companies to find the winners in this race towards a sustainable future.

In short, an ESG analysis focused on asset management, together with an in-depth knowledge of the framework of sustainable regulation, combined with a good financial analysis, will help us to find great investment ideas to which we can provide higher growth rates, lower capital costs, capacity to generate efficiencies and competitive advantages. Certainly this analysis has a bias toward mid-sized companies that are off the radar of the major rating organizations and without a prior sustainable label. But when you apply it, you can find some very interesting investment ideas. In addition, it is applicable to different long-term investment philosophies, whether the bias is toward more value, growth, or quality.

To conclude, I would just like to tip off the reader that the social taxonomy is now being cooked up in the European Commission kitchen.