No easy way out for the ECB

Redacción Mapfre

Ancient Greeks devoted a huge time and effort to solve the squaring of the circle. Ultimately, it was impossible with the means they had but those efforts contributed to make big progress in thought and science. Now, the ECB seems involved in a similar task: how to raise rates while preventing them from raising. Mrs. Lagarde is not probably very interested in metaphysics or abstract mathematics. But avoiding the fall of Italy in a debt trap while fighting inflation looks pretty much like a metaphysical challenge.

The problem

The ECB just announced the reinvestment of the PEPP redemptions to backstop spreads. This might work in the short term, not because of its amount (roughly 4bn per month), but because of the commitment they show. At the same time, they announced the creation of a new crisis tool. Once again, this is not a long-term solution, even less so under current circumstances. Kicking the can (far) down the road seems positive for markets over the longer term, but we still need a deeper solution.

We can summarize the key problem as follows. As the ECB turns more hawkish to fight inflation this means higher rates and less liquidity. This combination, together with challenging developments worldwide guarantees a sharp fall in growth in coming months. With higher rates and weak or negative growth, it turns highly likely that some very indebted countries (and companies) like Italy fall in the so-called debt trap (debt grows faster than GDP, thus leading the government to default over the long term). As investors think of this situation, they start to price it in an accelerating vicious circle, turning such thoughts into a self-fulfilling prophecy. This is what the ECB calls financial instability (or financial fragmentation), and is devoted to avoid at all costs as they consider it the main threat to the euro.

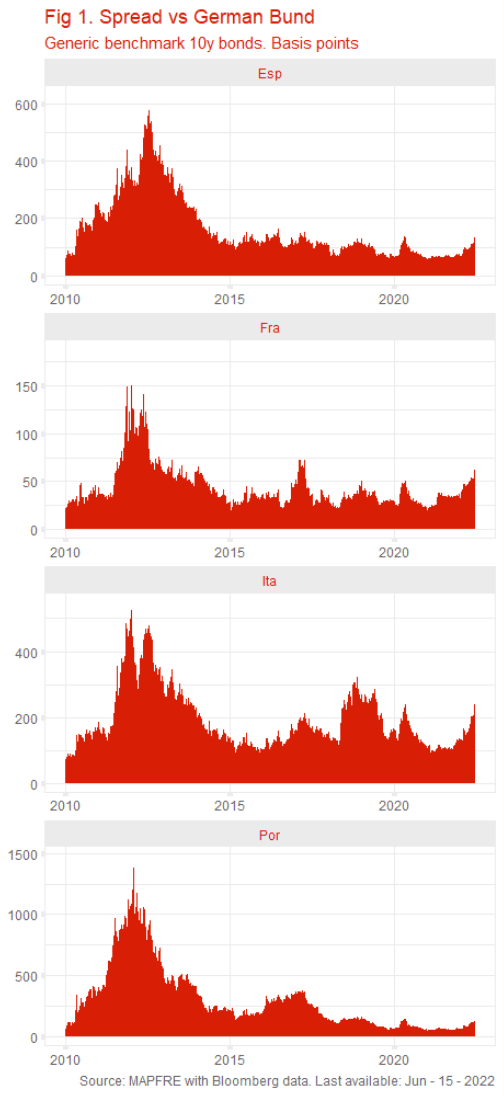

Thus, the ECB has three different enemies to fight at the same time: 1) the symptom, which is the evolution of spreads. So far, not yet as alarming as in other moments, 2) the real sickness, which is the indebtedness and lack of growth of some European countries. This can be traced back to very origin of the European Union, but particularly to monetary policies carried out since 2010. And 3) inflation itself, which risks amplifying the two above.

Each of the three needs different measures, usually contradictory. Thus, for example, using the asset purchasing mechanism to support spreads might compromise the reduction of liquidity needed to fight inflation, and would depreciate the euro, hence worsening the problem. Alternatively, letting inflation run would deepen growth issues, although it could dilute debt somewhat. On the other hand, winding down liquidity to fight inflation would tighten financial conditions much faster in Italy than in Germany. In other words, it seems that, under current circumstances, Germany needs a radically different monetary policy than Italy, which again talks of the very essential problems in the EMU2. In fact, this is the point the new tool should address, although that would guarantee a fierce German opposition.

All of the above could spill over into the political arena especially given the social impact of high inflation. It would be relatively easy for many populist parties all across Europe to capitalize inflation, lack of growth and the “inaction of Brussels”.

Conclusion: the likely evolution of the situation

There is no obvious solution. Now, from the comfortable position of looking at the rear view mirror, it seems that the ECB measures devoted to support financial stability in the period 2010-2021 might have been ill advised. But it is equally true that such measures were designed to support the situation temporarily until a deeper solution came from the political arena. Once again, Friedman’s adagio turned true: “Nothing is so permanent as a temporary economic program”. In fact, problem #2, the real sickness, cannot be solved by monetary authorities, but by a much wider political commitment. One very difficult to see unless under very extraordinary circumstances.

Although all of the above looks scary, we are still far from a full-fledged blow up. The current consensus points to a moderation of inflation in late 2022 and a limit to ECB hikes in the range of 1.5%. In the US, the situation seems parallel, with the Fed poised to interrupt its hawkish tone as growth weakens sharply at the same horizon. Should this be true, spreads would probably relax.

This means we depend completely on the evolution of the macroeconomic scenario, as always. Control of the situation by the ECB could be relatively high in monetary terms, but many macro or market developments cannot be controlled only with monetary tools. So far, the macro scenario looks not bad enough to panic. The new tool by the ECB seems thus more of a preparation to keep raising for some more months, than a real need.

All this leaves me with a big question I do not dare to answer yet: what if, by, say, October, growth is so weakened3, and market pressures become so high that the ECB must resort to its liquidity measures again? Let us wait and enjoy monetary imagination as we see the new tool. But in the end it comes down to whether the balance sheet expands or contracts. Both things cannot happen at the same time. A contraction is not good at all for asset prices and growth, but it is needed to fight an inflation that otherwise would harm markets and growth anyway.

The squaring of the circle took thousands of years to solve, and only in very complex and abstract mathematical terms. Monetary policy is not that complex, so probably if a solution looks like nonexistent, that is because it is.