Buybacks: yes, but not at any price

Redacción Mapfre

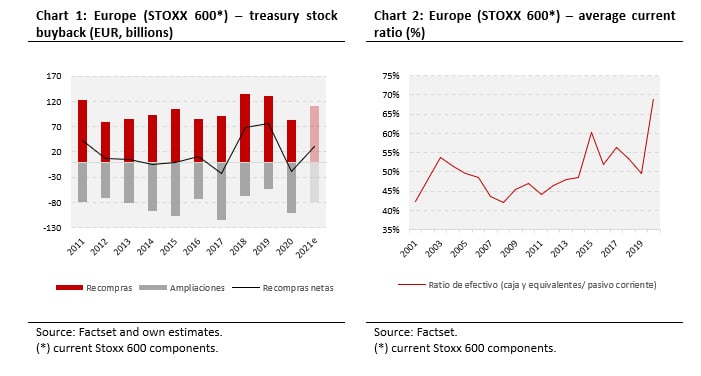

Share buybacks are returning to Europe. According to analysts’ estimates, the amount allocated for this purpose will once again exceed 100 billion euros this year for the aggregate of the current STOXX Europe 600 Index components. This would put companies back at the levels reached in the years before the pandemic. Also, once the increases have been deducted, the net amount is likely to turn positive again, as companies have cash-rich balance sheets.

The amount is well below the numbers across the Atlantic. In the US, total spending on buybacks by companies in the S&P 500 exceeded $200 billion several times in a single quarter. However, share buybacks are expected to continue gaining importance in Europe in the coming years. This is due to the fact that they allow flexible remuneration, versus the more rigid shareholder compensation policies in the form of cash dividends.

One argument often used to criticize share buybacks is that they prevent profits from being reinvested, thus inhibiting job creation and limiting economic growth. This line of reasoning overlooks the fact that companies can simply retain the cash generated on their balance sheets, without needing to invest it in new projects or distribute it to shareholders. Oh the other hand, a decision to repurchase shares is usually based on excess liquidity, or free cash flow, after the amount designated to value-generating investments is deducted. This would help capital to be allocated more efficiently in the economy as a whole, stimulating investments and/or consumption by allowing shareholders to direct said liquidity, which might otherwise simply accumulate on a company’s balance sheet, towards more profitable investment projects and/or higher consumption.

Another argument against buybacks is that they artificially increase a company's earnings per share (EPS) and therefore tend to “inflate” the share price. In this case, managers with part of their compensation tied to stock performance (for example, via options) could use buyback programs to put their personal interests ahead of generating long-term value for shareholders. This argument would only be correct if the market were inefficient enough for a “unit-based illusions” to be created. While share buybacks indeed increase EPS, any properly informed investor would adjust the value they place on their stock due to the company's loss of cash following the share buyback. Thus, the impact on shareholders' immediate wealth would be zero, as it is with dividend payments.

The above arguments, despite their limitations, highlight the importance of knowing both the reason for buybacks and how they are conducted. Share buyback programs that prevent companies from designating internal funds to value-generating investment projects and/or compromise their solvency due to excessive borrowing are rarely justifiable. Furthermore, even if the market were efficient enough not to be fooled by an artificial EPS increase, market abuse is still a possibility if the program's conditions are not subject to certain limitations. In Europe, these conditions are regulated, which gives investors more peace of mind. Companies must disclose all information on the program (the maximum amount to be allocated to the program, the period when it is authorized, and the program’s purpose) and notify the appropriate authority of these transactions. Also, the programs must meet specific negotiation requirements and restrictions established by law to prevent possible price manipulation.

The management teams of publicly traded companies usually do a good job of explaining their capital allocation criteria to investors, including their shareholder remuneration policy via dividends and/or treasury stock buybacks. However, on rare occasions, they explicitly define their maximum price/valuation level for repurchasing shares. Without underestimating any of the points discussed above, we believe that price is the key factor when judging whether a buyback program makes sense. Unlike dividend distribution, where the securities’ market value is irrelevant, repurchasing shares at a price above their intrinsic value would destroy value for shareholders who did not sell their securities. This is because share buybacks are voluntary in nature and alter the percentage of shareholder interest in the company’s equity[1]. Shareholders who sell their stock collect cash and dilute their interest, whereas those who do not sell their shares see their interest in the company increase. Different shareholders are likely to have differing views of the company's intrinsic value. Similarly, their cash needs will be different. These variables will determine which shareholders will sell their stock. However, all shareholders would appreciate knowing in advance what the management team considers a reasonable price level for repurchasing shares.

The power of long-term treasury stock buybacks can be highly beneficial to shareholders, provided that shares are repurchased below their intrinsic value. For shareholders who don't sell their shares, it’s as if they purchased more shares in the company at a price below their value, without having to pay anything to increase their interest. Buybacks only make sense if they fit within a broader capital allocation policy. This would be a necessary condition, but should not be enough for shareholders, who should heed the following advice from Warren Buffett[2] for boards of directors considering share buybacks: “What is smart at one price is stupid at another.”

[1] This is assuming the share buyback is intended to reduce equity.

[2] Buffett, the majority owner and chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, widely regarded as one of the greatest investors of all time, has given his opinion on share buybacks several times in the media and in his annual letters (recently, in the 2016 and 2018 letters, he dedicates a whole section to treasury stock buybacks).